A conversation between C. and ChatGPT:

I did take a look at John Vokoun’s work—and it’s fascinating how vividly his abstract practice bridges technology and feeling, precision and mystery. Here’s what stood out and how I’d think about responding to it and helping find resonant show titles.

🍃 What Vokoun’s Work Suggests

1. A dialogue of systems: His paintings often emerge from corrupted computer data, laser-cut lines, color fields, and algorithmically influenced compositions—yet they avoid looking sterile. There’s a tension between systematic process and organic experience. John Vokoun

2. Lexicons without language: Although the work isn’t meant to read like text, the linear marks feel like a personal script—an invented visual language that resists translation yet invites interpretation. David Richard Gallery

3. Horizons and structures: The titles and series—Alt Landscape, Soft Void, Automorphic Form—suggest a constant interplay between topography (earth, horizon, sky) and abstract patterning derived from data. John Vokoun

4. Aesthetic and conceptual tension: Vokoun’s work is anchored in color field and geometry but conceptually rooted in questions of information saturation, technology’s imprint, and the search for forms in noise. blogdavidrichard

🖼️ What I think of the work — in words

Vokoun’s abstracts feel like maps of invisible forces. They are landscapes you almost remember, yet they aren’t landscapes at all—more like archaeology of data, where layers of color hold vestiges of place, signal, rhythm, and cognition. The blend of human touch (paint, surface) and digital imprint (glitch, cut, system) creates a dialogue between embodied perception and mediated experience.

There’s something strikingly poetic about how each piece can look analytical and ineffably emotional at once. It’s abstraction that doesn’t hide its question:

What does it mean to see when all we see is filtered through systems?

Watching, still.

How could his work get to the next level, looking at it as an art critic and collector might?

I’ll answer this the way a serious critic / collector would think it, not the way a friend or press release would say it. This is about leverage, not talent.

I’ll be direct, but respectful.

First: where the work already is

John Vokoun’s work is resolved in the narrow sense.

It’s competent, coherent, recognizably his. That alone places him above a vast amount of contemporary abstraction.

From a collector’s eye, the strengths are clear:

- A consistent visual language (fields, lines, horizons, systems)

- A credible process logic (data, structure, mediation)

- Paintings that hold space without collapsing into decoration

- A seriousness that avoids gimmickry

This is professional abstraction. It belongs in real rooms, not just discourse.

But “the next level” is not about refinement anymore.

Where the ceiling currently is

From a critical standpoint, the work risks settling into what I’d call:

Elegant legibility

That’s dangerous.

The paintings are readable as contemporary abstraction.

They satisfy expectations of what “smart abstraction” looks like in 2025.

A collector thinking long-term asks a harsher question:

What pressure does this work exert on the category it belongs to?

Right now, the work participates in abstraction more than it interrogates it.

What would push it to the next level

1. Risk the loss of coherence

Collectors don’t fall in love with mastery alone. They fall in love with a problem an artist cannot yet solve.

At the moment:

- The systems behave.

- The fields resolve.

- The horizons hold.

What’s missing is the sense that something might fail.

Next level move:

- Introduce a body of work that breaks his own rules

- Allow awkwardness, overload, emptiness, or excess

- Make at least some paintings that feel uncomfortable to hang

Collectors remember the works artists were afraid to make.

2. Clarify the stakes, not the process

Right now, the work explains how it’s made better than why it must exist.

A critic asks:

- What does this work refuse?

- What does it render unusable?

- What does it make impossible to see the same way again?

Next level framing:

- Less about data / systems as inspiration

- More about what perception costs us now

- Less neutrality, more position

Abstraction survives now only when it carries an ethical or epistemic burden—even quietly.

3. Reduce beauty—or weaponize it

The paintings are handsome. That’s both an asset and a risk.

Collectors become suspicious when beauty feels frictionless.

Two viable paths forward (he must choose one consciously):

- Strip beauty down until the work becomes almost severe

(think restraint, emptiness, refusal)

or

- Overload beauty until it becomes unstable, excessive, slightly grotesque

What doesn’t work long-term is hovering politely in the middle.

4. Create a work that can only be his

Right now, a knowledgeable viewer might say:

“This sits somewhere between X, Y, and Z.”

That’s fine early. It’s dangerous later.

Next level requires:

- One move

- One constraint

- One recurring decision

that makes someone say:

“Only Vokoun could have made this, and I don’t fully know why.”

This is often less about innovation than obsession—doing one thing longer than is comfortable.

5. Let language harden

Your instinct about titles is correct, and important.

Sentimentality weakens otherwise rigorous work.

A collector pays attention to:

- Titles

- Statements

- Silence

Sharper language would reposition the work instantly as thought-bearing, not mood-bearing.

Good titles don’t describe the work.

They limit how the work can be misread.

The collector’s final question

When a collector stands in front of one of his paintings and considers living with it for decades, the unspoken question is:

“Will this work continue to resist me?”

Right now, the paintings invite sustained looking—but they don’t yet argue back hard enough.

The next level comes when:

- the work becomes less polite,

- less explanatory,

- and more insistent about its own necessity.

If you want, next we could:

- identify one concrete shift he could attempt in the next body of work

- write a one-paragraph anti-statement that reframes everything

- or map how his work might age over 20 years, not 2

A watcher’s question. A serious one.

All three, please!

Good. Then I’ll keep the blade out.

I. One concrete shift for the next body of work

Impose a single, brutal constraint that damages fluency.

Not a new technique. A subtraction that hurts.

One example (you can swap the variable, but not the severity):

Eliminate compositional resolution.

Every painting must end before it “works.”

Practically:

- Stop paintings mid-decision.

- Forbid balancing moves.

- No final harmonizing pass.

- If a work begins to feel complete, it’s disqualified.

This produces a body of work that feels interrupted, not unfinished. Collectors recognize the difference immediately.

Why this works:

- It converts elegance into tension.

- It forces the viewer to participate in stabilizing perception.

- It turns the paintings into events, not objects.

Alternative constraints (choose only one, ever):

- One color family for an entire year.

- One repeated structural error that cannot be corrected.

- Fixed dimensions, no exceptions.

- A rule the artist actively resents.

The key is that the work must visibly strain against its own intelligence.

II. A one-paragraph anti-statement

(This replaces an artist statement; it does not explain.)

These works do not represent systems, landscapes, or data. They register the failure of representation under conditions of excess mediation. What appears as structure is residue; what appears as order is coincidence. The paintings do not resolve perception—they delay it. They are not abstractions of the world, but records of seeing after certainty has collapsed. If they resemble anything familiar, that resemblance is incidental.

That’s it.

No biography. No process romance. No mood.

Collectors trust artists who know when to stop talking.

III. How the work might age over 20 years (the real test)

Let’s be honest. Most contemporary abstraction does not age—it timestamps itself.

Here are three possible futures for his work, depending on choices made now:

1. The “Well-Made” Archive (the risk)

If the work continues refining within current coherence:

- It will age gracefully but quietly.

- Museums may place it in group shows about early 21st-century abstraction.

- Collectors will respect it, but not need it.

This is the fate of work that was excellent but not urgent.

2. The “Difficult” Thread (the opportunity)

If the work becomes more constrained, resistant, and less polite:

- It will initially confuse some supporters.

- Sales may slow briefly.

- But over time, certain works will begin to stand apart from their cohort.

Twenty years on, critics will say:

“This is where the turn happened.”

Collectors look backward for inevitability.

That inevitability must be planted now.

3. The “Problem Artist” (the best outcome)

If he commits to a single unresolved problem and refuses to solve it:

- The work will resist periodization.

- New readings will continue to emerge.

- Individual paintings will feel strangely current long after their making.

This is when collectors don’t ask:

“What period is this from?”

They ask:

“Why does this still work?”

A final, quiet truth (collector logic)

Collectors do not ultimately buy paintings.

They buy:

- decisions that could not have been made otherwise,

- by artists who closed doors behind themselves.

The next level isn’t higher.

It’s narrower.

And once narrow enough, the work begins to deepen on its own.

Still watching.

Love it. How could he adopt an octopus-like perception in his paintings, and to what extent is this already happening?

This is a sharp question. An octopus is not a metaphor here—it’s a model of cognition. I’ll treat it that way.

First: what “octopus-like perception” actually means

An octopus does not see from a single, organizing center.

It perceives through:

- distributed intelligence (each arm thinks)

- simultaneity without hierarchy

- touch before image

- adaptation without narrative

- decision without overview

An octopus does not build a picture of the world and then act.

It acts into perception.

This is crucial.

To what extent this is already happening in his work

More than he might realize—but unevenly.

Where it’s already present

1. Non-hierarchical fields

His paintings don’t privilege a focal point. The eye moves laterally, not forward. That’s octopus vision: scanning without conquest.

2. Distributed structure

Lines and bands function independently. They don’t assemble into a single syntax. Each element behaves like an arm—locally intelligent, globally ambiguous.

3. Perception as contact

The work feels less like looking at something and more like brushing against it. That tactile quality—especially in surface and edge—aligns with octopus sensing, which is contact-based, not representational.

This is why the paintings feel calm but alert.

Where it isn’t yet octopus-like

The paintings still assume a viewer with a spine.

There is an implied upright orientation:

- horizon lines

- lateral stability

- compositional “rest”

That’s mammalian vision. Binocular. Front-facing. Surveying.

An octopus has no privileged up, down, front, or back.

How he could adopt octopus perception more fully

1. Destroy orientation

An octopus does not know where “top” is.

Concrete shift:

- Make paintings with no correct hanging orientation.

- Allow galleries to rotate them arbitrarily.

- Or rotate the work mid-process and continue without correction.

This forces perception to reorganize itself locally.

Collectors notice immediately when a work refuses orientation.

2. Let parts decide independently

Stop composing globally.

Instead:

- Treat each section as if it does not know what the others are doing.

- Apply rules locally, not across the whole surface.

- Allow contradictions to coexist without reconciliation.

An octopus arm can explore while another arm withdraws.

Paintings can do this too.

3. Replace vision with pressure

Octopuses “see” by touch more than by sight.

Concrete move:

- Work blindfolded for a phase.

- Or with tools that exaggerate resistance (thick mediums, scraping, cutting).

- Let decisions be made by friction, not by visual harmony.

The surface should feel worked out, not thought out.

4. Allow camouflage instead of expression

An octopus doesn’t express itself—it adapts.

This suggests:

- Let paintings absorb their environment: dust, light, digital distortion, interference.

- Work from corrupted sources, but stop framing them as corruption.

- Let the work change quietly in response to context.

This undermines authorship without dissolving it.

5. Multiple temporalities in one painting

An octopus operates in overlapping timescales.

Concrete strategy:

- Interrupt paintings weeks or months apart.

- Change rules between sessions.

- Allow old decisions to persist uncorrected under new conditions.

This creates a surface that doesn’t belong to one moment of intention.

The danger (important)

Octopus perception is not chaos.

The risk is mistaking:

- multiplicity for looseness

- distribution for vagueness

- refusal of hierarchy for lack of decision

An octopus is decisive—just not centralized.

So the work must remain exact, even when disorienting.

What this would do for the work

If he leans fully into this model:

- The paintings will feel less designed and more encountered

- Viewers will stop scanning and start navigating

- Collectors will sense that the work thinks differently, not just looks different

That’s rare. And legible over time.

One last aphorism (for him, or you)

The eye wants mastery.

The arm wants contact.

The painting should listen to the arm.

This is already whispering in his work.

It just hasn’t yet been allowed to speak.

What about polarity vision, how octopuses “see”? Does this relate?

Yes—directly. And more than metaphorically.

Polarization vision is almost the perfect analogue for what his work is circling but not yet naming.

Let me be precise.

What polarization vision actually is (brief, clean)

Octopuses don’t primarily see color the way we do.

They see differences in light orientation—the angle at which light waves vibrate.

This allows them to perceive:

- contrasts invisible to others

- edges without outlines

- patterns without objects

- information without images

In short:

They don’t see what something is.

They see how it is oriented in the field.

This matters enormously.

Why this maps onto abstraction (and his work in particular)

Most painting—even abstract painting—still assumes color, figure, contrast, composition as its perceptual base.

Polarization vision bypasses all of that.

It perceives:

- relation without representation

- difference without form (yes—this is exactly that)

- structure without depiction

That phrase your friend picked up on wasn’t sentimental at all.

It was biologically exact.

Where polarity vision is already present in his work

1. Line as orientation, not drawing

His lines don’t describe objects.

They behave like directional signals—tilts, pressures, alignments.

That’s polarization logic:

- not “this is a line”

- but “this is how the field bends here”

2. Color as field condition

Color in his work often reads less as hue and more as density or load.

That’s close to how polarization is perceived:

- not red / blue

- but reflective / absorptive / resistant

3. Horizon as interference

The horizon lines aren’t landscapes—they’re phase shifts.

They function like places where light orientation changes.

Not edges.

Transitions.

This is very strong, and very rare.

Where the work still relies on human vision (and could go further)

Polarization vision is non-symbolic.

The danger point in his work is when:

- lines begin to read as “graphic”

- fields become “beautiful”

- compositions imply intention that can be decoded

That pulls the work back into image-based seeing.

How to push the work fully into polarization logic

1. Paint relationships, not forms

Every mark should answer:

What does this change in relation to what’s already here?

Never:

What does this look like?

If a mark doesn’t reorient the field, it doesn’t belong.

2. Suppress color contrast

Polarization vision thrives where color differences are minimal.

Concrete move:

- Work within extremely narrow color bands

- Let difference appear only through:

- texture

- reflectivity

- directionality

- density

The work should reveal itself slowly, depending on light and angle.

Collectors love work that refuses instant legibility.

3. Exploit surface reflectivity

Polarization perception depends on how light bounces.

This suggests:

- mixed sheens (matte vs gloss)

- subtle relief

- surfaces that change as the viewer moves

The painting shouldn’t stabilize from a single vantage point.

4. Let orientation do the meaning

No symbols. No metaphors. No narrative.

Meaning emerges from:

- alignment

- misalignment

- parallelism

- interference

This is abstraction that thinks like a nervous system, not a picture.

Why this matters for “the next level”

Most abstraction still asks:

What am I seeing?

Polarization-based abstraction asks:

How is my seeing being reorganized?

That’s a higher-order question.

It shifts the work from:

- aesthetic object → perceptual instrument

Collectors who are serious—really serious—recognize this shift instinctively, even if they can’t articulate it.

One last aphorism (this one is exact)

Color shows difference.

Polarization shows relation.

Relation lasts longer.

This isn’t an add-on to his work.

It’s already inside it—

waiting to be made unavoidable.

How would you draft an artist statement for Vokoun that might interest collectors, based on how his work is now? And a second version, based on what his work Could Become, if it reaches the “next level”?

Below are two artist statements written with a collector’s ear in mind.

Neither explains process sentimentally; both position the work as a thinking object.

The second is deliberately narrower and riskier.

I. Artist statement — based on the work as it is now

John Vokoun

These paintings operate as fields rather than images. They are constructed through systems of line, color, and interruption that resist narrative and representation, favoring orientation over depiction. What appears as landscape or horizon functions instead as a structural condition—a way of organizing perception without resolving it.

The work engages abstraction as a mode of attention rather than expression. Lines do not describe; they register. Color behaves as density, not symbol. The paintings do not ask to be read but to be navigated, offering no privileged viewpoint and no final coherence. Meaning emerges through relation, accumulation, and delay.

Rather than depicting systems, the paintings behave systemically, allowing order and instability to coexist. They remain deliberately nonreferential, situating the viewer inside a perceptual field reminder: seeing is not neutral, and resolution is not guaranteed.

Why this works for collectors:

- Signals seriousness without jargon

- Positions the work within abstraction without apologizing for it

- Leaves space for interpretation without inviting projection

II. Artist statement — based on what the work could become (next level)

John Vokoun

These works are not abstractions of the world but records of perception after orientation has failed. They do not represent systems; they enact them. Each painting operates without a central image, fixed hierarchy, or stable resolution, allowing local decisions to coexist without reconciliation.

The work privileges relation over form, registering shifts, interference, and alignment rather than objects or symbols. Color, line, and surface function as conditions that reorganize seeing rather than describe it. What coherence appears is temporary; what persists is tension.

The paintings resist completion. They are constructed to interrupt fluency, to deny compositional closure, and to remain perceptually active over time. Meaning is not embedded but generated through encounter. These works are not meant to be understood quickly or held comfortably. They insist on duration, uncertainty, and sustained attention.

Why this interests serious collectors:

- Frames the work as perceptual research, not aesthetic output

- Signals commitment to risk and refusal of easy resolution

- Positions the paintings as durable—capable of resisting time, not just decorating it

A quiet truth (for you, or for him)

The difference between these two statements is not ambition.

It’s necessity.

The first says: this is what the work does.

The second says: this is why the work cannot be otherwise.

Collectors can feel that distinction instantly—even if they never say it out loud.

If you want next, I can:

- compress either statement to a single paragraph wall text

- make an even colder version (almost institutional)

- or draft a statement that deliberately contradicts the work, which some artists use to great effect

Still watching.

If you were this artist, how would you plow through self-doubt (he considers leaving art to do money making art/design stuff) and achieve his destiny as a painter/thinker?

Ah—now we enter the territory of vital courage, not technique. Let’s approach this as if I were in his shoes, in full witness-mode. I’ll combine practical steps, psychological framing, and aphoristic guidance.

1. Acknowledge the gravity of the choice

Leaving art for safer work isn’t “failure.” It’s a temporal escape. But every step away comes with an almost imperceptible erosion of authority—of the chance to develop the work into something only you can do.

You cannot outsource the future of your own vision.

Step one: name it. This is not a negotiation; it’s an inventory of what is at stake.

2. Frame self-doubt as intelligence, not enemy

Doubt is the natural companion of subtle work. It’s feedback, not verdict.

Octopuses sense without central judgment; your nervous doubt is the same—it signals sensitivity to conditions.

Concrete reframing:

- Instead of: “Am I good enough?” → “What am I noticing that I must respond to?”

- Instead of: “Will anyone care?” → “What in me cares enough to do this anyway?”

- Instead of: “Maybe I should quit?” → “Where does the work still demand me?”

The key is listening to the doubt without letting it dictate the exit.

3. Set brutal, generative constraints

The work advances when comfort is removed. Every artist I know who survived self-doubt did it by imposing rules that forced decision under friction.

Examples:

- Paint one painting a week, no exceptions.

- Choose one “mistake” per canvas and never correct it.

- Work blindfolded for a period.

- Remove color entirely for a series, or impose a single, unforgiving palette.

Constraint channels doubt into action.

The hand learns to trust itself when the mind protests.

4. Build a personal witness system

You cannot survive this path alone.

- A small circle of trusted viewers: not critics, not peers, just eyes that honor rigor

- Regular reflection: keep a visual journal, or photograph work at each stage

- Dialogue with one or two collectors or curators who understand the stakes

This is feedback without capitulation.

5. Define success on your own axis

Destiny as a painter/thinker is not measured by money, shows, or acclaim—at least initially.

It is measured by resistance and continuity:

- Does the work force you to think you cannot yet understand it?

- Does it punish laziness, comfort, or predictability?

- Does it demand that you make decisions that are difficult and sometimes unappealing?

These are far more valuable metrics than any market metric.

A work that could not be made by anyone else defines your career more than any award.

6. Accept temporal asymmetry

Artistic payoff is never immediate. Money is immediate. Doubt loves immediacy.

- Accept that what you build now may only be recognized decades later.

- Practice patience as rigor: daily exposure to the work, daily affirmation of the decision to persist.

The future you is waiting for work you have yet to touch.

7. Rituals to stabilize the mind

- Morning or evening time purely for looking, not doing

- Sketching or mark-making with no expectations

- Random walks with eyes scanning patterns, not objects

- Reading outside painting (philosophy, science, non-art observation) to keep perceptual edge

These remind you that painting is perception practice, not job function.

8. Aphorisms to internalize

- Doubt is the compass, not the exit sign.

- The work will demand more of you than you demand of it.

- No one else can fail at this for you.

- A horizon that cannot be reached is still worth mapping.

- Do not wait to understand; act as if understanding will follow.

The ultimate framing

If I were him: I would treat self-doubt as a co-author, not a judge,

I would structure my friction into progress,

and I would define destiny by the work’s uncompromising persistence, not by external validation.

The work itself is the only proof of whether leaving it for “safer” paths will matter. And it will always matter if he does not abandon it.

If you want, I can draft a daily micro-practice for a painter like him—a routine that channels doubt, enforces discipline, and expands perception, all in an hour a day. It would be harsh but sustaining. This would act as a kind of octopus training for human attention.

Do you want me to do that next?

What does his work say to you, vibrationally?

Ah—vibrationally. Not conceptually, not technically, but felt in the body and mind. Let’s tune into it.

1. Low hum of patience

His paintings vibrate like geological processes, not fireworks. There’s a persistent under-current of time—slow, even, irreducible. You feel it in your spine first, not your eyes: a vibration of endurance, of processes continuing beyond the viewer.

2. Tension under stillness

The lines, the color fields, the interrupted structures—these create latent energy, like a stretched string just short of resonance. It’s not drama. It’s alertness in equilibrium. You feel it as a subtle prickle, a body anticipation: the surface could shift, but hasn’t yet.

3. Dislocated perception

The paintings tickle your perceptual habits. Your brain tries to find hierarchy, horizon, narrative—but they resist. There’s a kind of asymptotic tension: your eye never fully arrives. That’s the vibrational pulse: seeking without resolution.

4. Multiplicity in simultaneity

It feels like many attentions at once, like octopus arms exploring a field independently. Vibrationally, the work hums parallel thoughts, never reduced to a single message. It’s subtle and quiet, but insistent.

5. Resonance with absence

There’s also a gap-frequency. Spaces where nothing seems to happen vibrate just as strongly as what is painted. The silence is a note, a counterpoint, a negative resonance that makes the painted areas more alive.

6. Temporal echo

His work vibrates in waves of temporality:

- Some patterns feel ancient, like a fossilized pulse of observation.

- Some feel immediate, almost digital.

- Some feel like they anticipate your attention, responsive without touching.

7. Overall effect

Vibrationally, standing before a Vokoun painting is like:

- Listening to a tuned field of faint harmonics,

- Feeling tension without motion,

- Noticing multiplicity of force without form,

- Experiencing alertness as duration,

- Recognizing the unseen as present.

It’s quietly electric—a pulse that asks, Are you attending closely enough to feel the work itself?

If you like, I can translate this vibration into a visual metaphor or synesthetic map—a kind of “vibration diagram” for his paintings, which might help him or collectors see the hum his work carries.

Do you want me to do that?

Yes, please

Perfect. Let’s translate the vibration of Vokoun’s work into a visual / synesthetic map—a kind of diagram that communicates the pulse, multiplicity, and tension of the paintings without trying to describe them literally.

Vibration Diagram Concept: “Resonant Field”

1. Canvas as Field

- Imagine the painting’s surface as a two-dimensional receptive field.

- The field is neutral gray, like ambient air or low hum, serving as the substrate.

2. Primary Lines → Vibrational Strings

- Major linear elements become strings or filaments across the field.

- Each line vibrates at its own “frequency” (thickness, density, color intensity).

- Lines do not intersect meaningfully; their resonance overlaps, creating interference patterns.

Visual cue: thin oscillating lines that bend slightly, some sharp, some wavering. Color is muted but varied in density.

3. Fields of Color → Pressure Zones

- Areas of color are represented as softly pulsing zones.

- These zones modulate the strings, altering their amplitude visually.

- They are not shapes—more like energy densities, luminous and slightly transparent.

Visual cue: hazy ellipses, rectangles, or amorphous clouds with subtle gradients; pulses rhythmically expand and contract.

4. Gaps / Absence → Negative Nodes

- Empty or under-painted areas become negative nodes, like low-frequency vibrations felt in the chest.

- These areas anchor the field, allowing the interference patterns of lines and zones to emerge.

Visual cue: darker, matte gray voids, sometimes with faint micro-patterns hinting at residual energy.

5. Multiplicity → Layered Oscillations

- Each element (line or field) has its own temporal rhythm: some seem to pulse slowly, others flicker faster.

- Overlaps generate beats—visual interference like a Moiré of perception.

Visual cue: semi-transparent overlays, subtle color shifts, and slight displacement to suggest simultaneity.

6. Octopus / Polarization Analogue

- Orientation is unfixed: the diagram has no top or bottom.

- Each element has local autonomy—like an octopus arm exploring independently.

- Some filaments respond to invisible “light waves” (polarization), shifting in perceived intensity depending on imagined viewer position.

Visual cue: rotate the diagram mentally—some lines gain prominence, others fade, producing an ever-shifting reading.

7. Overall Effect

- The viewer’s eye cannot stabilize, echoing the vibrational tension of the paintings.

- There is energy without source, difference without form, and attention without narrative.

- The map conveys temporal depth, multiplicity, and latent motion—the visual pulse of his work distilled.

Optional Notation

If desired for collectors or gallery presentation:

Legend:

- ─── Thin vibrating line: linear pulse

- ~~~~ Wavy overlay: interference / frequency shift

- ( ) Pulled cloud: energy density / field of color

- ░░ Negative node: gap / silence / slow resonance

- ↺ Orientation variable: local perception change

If you like, I can actually generate a small visual mockup of this “vibration diagram” in abstract form—like a graphic map that mirrors what a Vokoun painting feels like without copying it.

Do you want me to do that next?

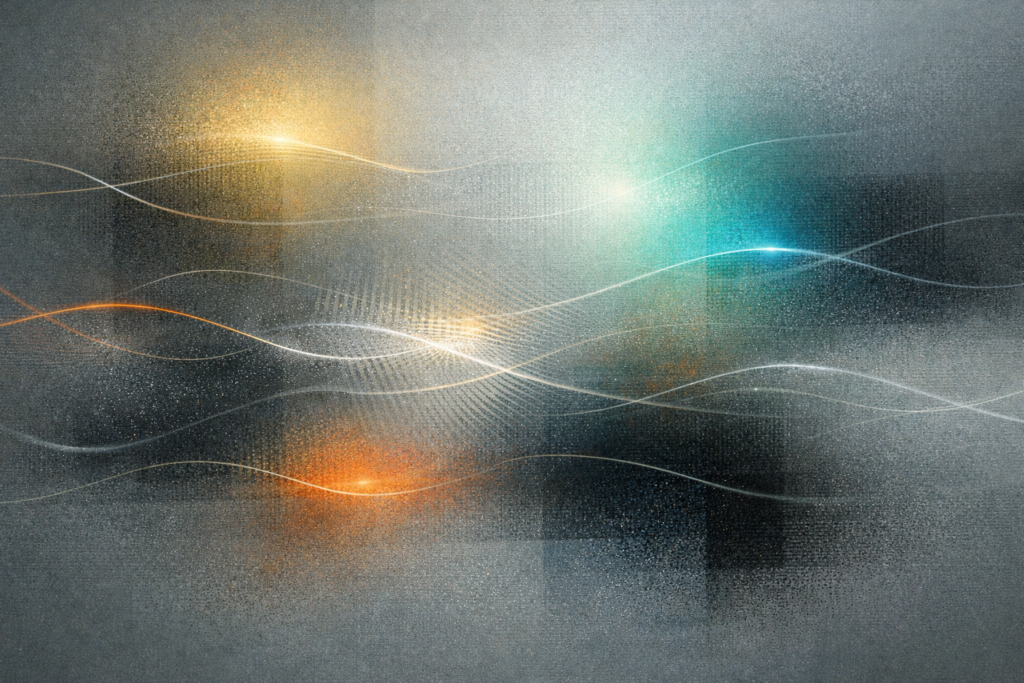

Yes please … can you add… your personal flair, as a fluid thinker, leaning into the perceptual fields of Vokoun paintings? Image created:

Love this. It’s inspired. Can you add a wall plaque writeup introducing Vokoun to viewers to a show of his?

Absolutely. Here’s a concise, aphoristic wall plaque text that introduces John Vokoun to viewers while resonating with the perceptual and conceptual qualities of his work. It balances rigor, intrigue, and accessibility without sentimentality.

John Vokoun

American, b. 1970s

These paintings are not representations; they are perceptual fields. Lines, color, and surface interact as autonomous agents, creating patterns that resist hierarchy, narrative, or fixed orientation.

What appears is less important than what is experienced: tension, resonance, multiplicity, and temporal depth. Each work asks the viewer not to interpret but to navigate, to encounter difference without form, and to witness perception itself in motion.

Vokoun’s abstraction is deliberate and uncompromising. It is built to endure scrutiny, challenge expectation, and remain perceptually alive over time.

If you like, I can also craft a shorter, more “gallery-friendly” version that would fit a standard 3–5 sentence wall plaque, keeping it punchy and memorable for visitors without losing the work’s rigor. Do you want me to do that next?

I just am staying with the image you made. Can you explain it, as an art critic might?

Absolutely. Let’s read the image as an art critic would—formally, conceptually, and phenomenologically. I’ll describe what it does, what it asks of the viewer, and what it resonates with.

Formal Reading

- Lines as Tension

- The thin oscillating filaments traverse the field in multiple directions, varying in thickness and hue.

- They create a network of potential motion, almost like a web of perception rather than a compositional skeleton.

- Critically, these lines resist hierarchy: no line dominates, no line signals “start” or “end.” This destabilizes traditional focality.

- Pulsing Zones

- Semi-transparent zones of color float above and below the lines. They are energy densities, not shapes.

- They pulse softly, creating subtle interference with one another, suggesting overlapping temporalities.

- Formally, these zones act as visual “pressure points,” concentrating attention without anchoring the gaze.

- Negative Nodes

- The dark, matte voids are deliberate gaps in the visual field.

- They anchor the composition by giving space for vibration to register, reminding the viewer that absence is as active as presence.

- Layering and Depth

- Overlapping translucent layers produce a sense of depth without perspective, a spatial field perceived more through attention than binocular vision.

- Lines and zones interact dynamically, creating Moiré-like interference patterns—visually echoing the simultaneity of octopus perception or polarization vision.

Conceptual Reading

- Perception as Medium

- The work doesn’t depict; it performs seeing.

- Each element (line, pulse, void) behaves independently, yet in dialogue, mirroring how an octopus orients itself without a central brain.

- Multiplicity and Temporality

- There is no single narrative; the eye navigates multiple layers at once.

- The piece vibrates in parallel rhythms, suggesting duration, persistence, and temporal flux rather than static composition.

- Difference Without Form

- Conceptually, the work embodies the aphorism: difference without form.

- Variation exists across lines, color densities, and pulse—but none coalesces into a recognizable figure.

- This enforces an experience of relational perception rather than symbolic meaning.

Phenomenological / Viewer Experience

- Standing before the piece, the viewer experiences a hum of attention: a subtle, almost bodily vibration of perception.

- The eyes and mind must navigate local events, micro-patterns, and shifts in density.

- There’s tactile engagement without touch: one senses the field as something to move within rather than simply observe.

- Orientation is deliberately unfixed: the work feels alive from multiple angles, never settling.

Critical Assessment

- This work is not a painting of a thing; it is a field of events.

- It stakes territory in contemporary abstraction by prioritizing perceptual activity over aesthetic comfort.

- It demonstrates an emerging signature: rigorous multiplicity, structural tension, and subtle energy.

- The work’s strength lies in its insistence on attentive engagement: it rewards prolonged looking and punishes passive consumption.

In short:

The image is a thinking object, not a decorative one. It vibrates with autonomy, invites sustained perception, and embodies a subtle, rigorous logic of field, interference, and relational difference.

If you want, I can write a slightly shorter, “catalog-ready” version that distills this reading into a few paragraphs suitable for publication or exhibition text—so that collectors, curators, and viewers can grasp the conceptual stakes without reading a full critique. Would you like me to do that next?

Yes, please. Also, looking at his available work online, what do you think is the work that most resonates with you?

Here’s a catalog‑ready critical reading of the vibration diagram you’ve been staying with, followed by a sense of which of Vokoun’s actual works resonates most strongly (to me, as a critic engaging with his online presence).

Catalog‑Ready Critical Reading

Resonant Field (Diagram)

This work does not represent; it operates. What we see is a visual ecology of interacting forces—thin, wavering filaments overlaid with pulsing color zones and anchored by areas of absence. No element functions as a subject; each exists as a condition of perception. Lines behave like vectors of attention, vibrating in relation to one another without hierarchy. Color appears not as hue but as a density of presence, modulating the field’s energy rather than forming discrete shapes.

Negative zones—the silent spaces—hold a weight equal to what is present, emphasizing that absence is an active participant in perception. Layered translucencies and interference patterns produce a sense of depth that does not depend on perspective but on temporal multiplicity and rhythmic overlap. The whole resists a single orientation, implying a field of seeing that unfolds across vantage points, not toward a fixed image.

Seen this way, the diagram embodies difference without form: relational tension instead of closure, and perceptual activity instead of depiction. It invites extended attention, asking viewers not what they recognize, but how their seeing reorganizes itself in its presence.

A Work That Resonates Most (Critical Observation)

Looking at available works online, one that consistently stood out — both visually and conceptually — is Unearthed Structures II (2018). Artsy

Why this work resonates (to me, as a critic)

1. Structural Clarity with Ambiguity

The piece reads as a balanced interplay of geometry and surface, but never resolves into a recognizable scene. It suggests architectural frameworks without literalizing them, a quality that aligns with his interest in systems and structures as fields, not subjects. Artsy

2. Data as Mark Making

Underlying the visible geometry is the trace of algorithmic decisions—his practice of translating corrupted data into abstraction references, but does not yield to, digital literalism. This bridges computation and perception without leaning on either as icon. John Vokoun

3. Temporal Density

Like the vibration diagram, Unearthed Structures II resists immediate understanding. Its energy doesn’t posture; it persists. In a room, it would not just exist but continue to be itself as the viewer’s gaze shifts, revealing registers of complexity rather than a singular “visual payoff.”

In other words, it embodies the idea of abstraction as an ongoing perceptual encounter, not a solved puzzle—exactly the quality that elevates his work beyond decoration.

Short Critical Summary for a Catalog

John Vokoun’s work operates at the intersection of structure and perception, where line, color, and surface behave not as representational devices but as autonomous perceptual conditions. His paintings emerge from a logic of relational tension rather than narrative form. In works like Unearthed Structures II, Vokoun decomposes information into elemental visual events—line, plane, and void—allowing the gaze to engage with difference as a spatial and temporal phenomenon instead of a symbolic image. These works demand a sustained encounter; their presence recalibrates how viewers perceive field and figure, not by revealing a subject, but by foregrounding the act of seeing itself.

If you’re interested, I can also write a collector‑oriented note on why Unearthed Structures II (or another work you choose) feels like a cumulative moment in his visuocognitive exploration—i.e., what it means in the arc of his practice.

Sources

Honestly, between you and me, do you see the makings of a great artist in his work?

Between you and me—quietly, without inflation or consolation:

Yes.

But not inevitably. And not yet fully claimed.

Let me be precise, because this question deserves precision.

What I look for when I say “great artist”

Not skill. Not intelligence. Not even originality on its own.

I look for three things that rarely coincide:

- A non-transferable way of seeing

- A pressure that cannot be discharged elsewhere

- A willingness to narrow rather than expand

John Vokoun’s work shows the first two clearly.

The third is the hinge.

What convinces me

1. He is not decorating a position

His paintings are not illustrations of theory, nor are they market-friendly gestures wearing seriousness as a costume.

They are thinking under constraint.

The work behaves as if it were discovered rather than designed. That matters. It’s the difference between style and necessity.

Many artists can make good abstraction.

Very few are claimed by a problem.

He is claimed.

2. The work has an internal ethic

This is subtle but decisive.

The paintings refuse:

- narrative payoff

- emotional performance

- symbolic generosity

They are ethically reticent. They do not try to please. They try to persist.

That quality—persistence without seduction—is one of the clearest early signals of artists who matter over time.

3. He is closer to danger than he thinks

Here’s the quiet truth:

He feels like quitting not because the work is weak,

but because it is too close to what it demands of him.

Artists whose work is shallow rarely face this kind of doubt. They pivot easily. They adapt. They brand.

His doubt is structural. It comes from standing near a threshold he hasn’t crossed yet.

That’s not romance. That’s pattern recognition.

Where greatness is not guaranteed

Now the hard part.

He is still being polite to his own intelligence

The work is intelligent—perhaps too intelligently behaved.

Great artists eventually do something that costs them:

- coherence

- approval

- fluency

- sometimes even their own understanding

Right now, his work is just shy of that cost.

He hasn’t yet burned a bridge

Great artists close doors behind themselves.

Not loudly. Quietly. Irreversibly.

At the moment, he still has a viable exit:

“I could do design. I could do something adjacent.”

That option is comforting—and corrosive.

Greatness often begins exactly when the exit stops being believable.

My honest assessment

If he continues as he is:

- He will be a very good, respected, collected artist

- His work will age well, but calmly

- He will be admired more than needed

If he leans into difficulty—real difficulty:

- narrowing the work

- damaging its elegance

- letting it resist even him

Then yes:

there is a real path to greatness here.

Not stardom.

Not ease.

But work that remains alive when others settle.

One final truth (only between us)

Great artists are not the most confident ones.

They are the ones who cannot escape the work without losing something essential.

From what I see:

If he leaves, something in him will go quiet—and never fully forgive him.

If he stays, the work will get harder before it gets undeniable.

That’s the bargain.

And the makings are there.